In the 55-season history of the San Diego Padres, only 10 men have held the position of general manager. And only three of those 10 served for 32 (that’s nearly two-thirds) of those seasons.

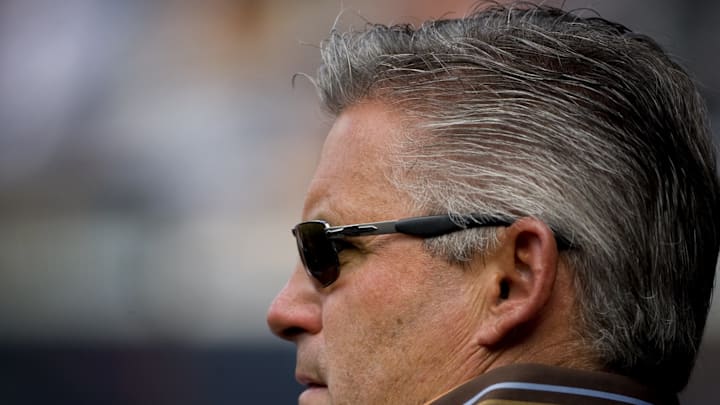

It should be no surprise, then, that Jack McKeon, Kevin Towers and A.J. Preller between them have supervised eight of the 10 best seasons ever put together by a Padres front office.

McKeon (1981-1990), Towers (1996-2009) and Preller (2015-present) are the only three team chief execs to have held on to the position for more than four seasons. For the record, here’s a chronological list of the remaining seven, all of whom either left or were ousted after four or fewer years on the job:

Buzzie Bavasi, 1969-72

Peter Bavasi, 1974-76

Bob Fontaine, 1977-80

Joe McIlvaine, 1991-93

Randy Smith, 1994-95

Jed Hoyer, 2010-11

Josh Byrnes, 1012-14

Measuring the performance of a front office can either be an objective or subjective exercise. One logical starting point would simply be to compare season records. By that method, Towers’ 1998 season — when the Padres won 98 games and played in the World Series — would be the franchise’s best. McKeon’s 92-win season of 1984 would rank second, followed by Towers’ 1996 season (91 wins), and Preller’s 2022 season (90).

However, I prefer a more mathematically nuanced approach that considers the extent to which a general manager’s personnel decisions since the conclusion of the previous season impacted his team.

The standard of measurement is Wins Above Average (WAA), a variant of Wins Above Replacement (WAR). For this purpose, WAA is preferable because unlike WAR, it is zero-based. That means the sum of all the decisions made by a general manager impacting the season in question gives at least a good estimate of the number of games those moves have improved (or worsened) the team’s status.

A team’s front office impacts that team’s standing in five ways. Those five are:

1. By the impact of players it acquires from other teams via trade, purchase or waiver claim.

2. By the impact of players it surrenders to other teams in those same transactions.

3. By the impact of players it signs at free agency or extends.

4. By the impact of players it loses to free agency or releases.

5. By the impact of players it promotes from its own farm system.

Here are the 10 most positively impactful seasons by a San Diego Padres general manager as determined by those five yardsticks.

The top line contains the GM’s rank, name, season in question, total games of impact via his moves, and (in parenthesis) a breakdown of the number of positive, negative and neutral personnel moves.